Breadcrumbs: Philosophy/ItRaP/Epistemology/Knowledge

Reframing Claim:

Let’s consider Knowledge and Belief as mutually exclusive sets.

The Traditional Structure

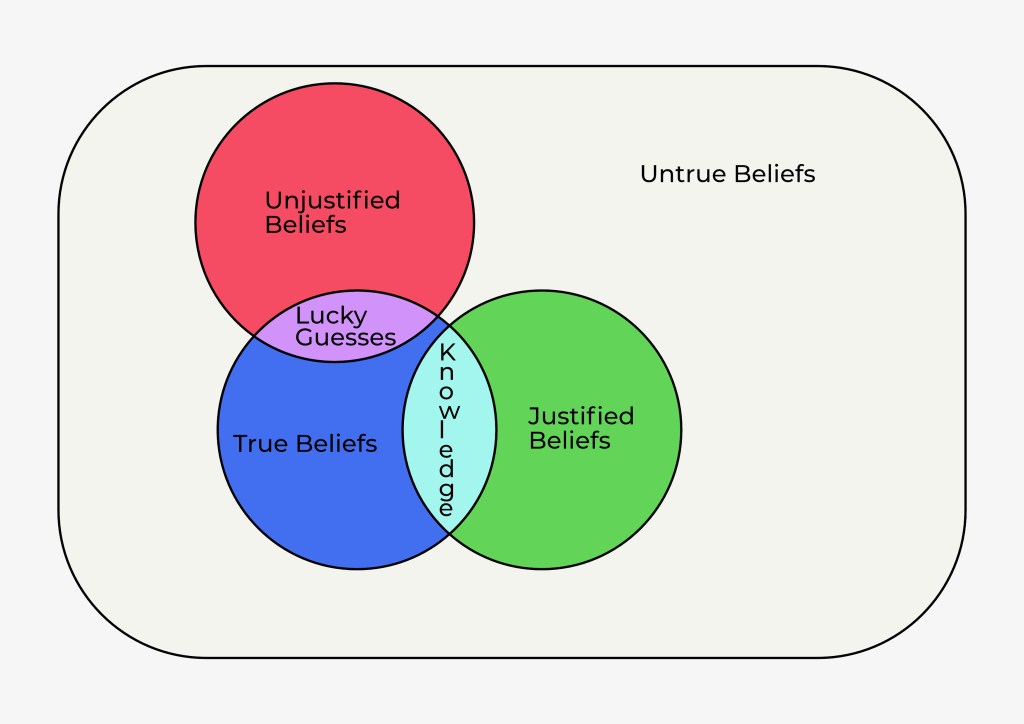

In traditional western philosophy knowledge is usually considered to be true justified belief. It can be shown in the following Venn diagram.

All of our beliefs are taken as a universal set. True beliefs are a subset of all of our beliefs with everything outside automatically becoming untrue beliefs. We also have two sets for all our justified beliefs and unjustified beliefs. The pairs of true-untrue and justified-unjustified beliefs are by definition mutually exclusive. But justified beliefs can intersect with true beliefs. This is called as knowledge.

When we have a belief that is true and we also have a justification for believing it, we are said to have knowledge. There can also be an intersection between unjustified beliefs and true beliefs. These are beliefs that we have no justification for, but they happen to be true. We can consider them lucky guesses. Just because they’re true doesn’t make them knowledge. Knowledge only occurs when we are justified in holding our beliefs.

Problems of the Traditional Structure

There are certain problems with structuring our beliefs and knowledge in this way. Let’s go over some of them one by one.

Gettier Cases

The most popular issue with this definition is often called the Gettier problem, named after philosopher Edmund Gettier who showed, by example, a scenario in which a person could be said to hold a true justified belief but it’s clear that it could not be considered knowledge. These kind of cases were known and discussed by older western and Indian philosophers such as Dharmottara and Peter of Mantua as well so this isn’t a new issue.

Farmer’s Sheep

Here’s an example of a such a case. There’s a farmer standing outside his field which stretches as far as his eye can see. In the distance he sees a white ball of fluff all curled up in the grass. He says, “I know there is one sheep in the field.”

Unbeknownst to him, what he is seeing is not a sheep but his sheep dog who looks like a sheep from a distance. Also unbeknownst to him, there is a sheep sleeping right behind the sheep dog, but he can’t see it at all.

The farmer’s statement is true. There is one sheep in the field. He is justified in believing this because he thinks he can see one sheep. This belief is both true and justified from his point of view but we know that he is wrong in his justification, therefore it would be wrong to say that he has knowledge about how many sheep are in his field.

Smith, Jones & Brown

Another example, as given by Edmund Gettier is as follows. Smith has a friend called Jones and a friend called Brown. He knows that Jones owns a Ford. He has seen Jones’ Ford. He’s ridden with Jones in his Ford. He has full justification to believe that Jones has a Ford. Smith says, “Either Jones owns a Ford, or Brown is in Barcelona.”

He knows this statement is true because Jones owns a Ford. He has no idea where Brown is but he doesn’t need to know that because it’s an either/or statement and he knows that one of those is true, therefore the entire statement is true.

Unbeknownst to Smith, Jones has recently sold his Ford and also unbeknownst to Smith, Brown has moved to Barcelona to be with his girlfriend. So his statement is still true, but not for the reason he thinks. Smith is true and Smith has justification but can we say that Smith has knowledge?

What such cases show is that true justified belief is an incomplete definition at best.

The Knowledge of Animals and Plants

Another issue with such a structure is that it characterizes knowledge completely within beliefs. Beliefs are thought constructs that a person holds in their head. But then does that mean that only humans can have knowledge?

What about animals and plants? What about the instinctive knowledge that animals have? What about the ability of animals to learn to do stuff or use tools or solve puzzles? Is that not acquired knowledge? If yes, then do animals have beliefs? Can animals construct abstract thoughts in their head? Is language based thoughts the only way to have knowledge, or for that matter, beliefs?

All these questions raise important issues with this structure. Philosophers have tried to resolve these issues in various ways. Some say that beliefs don’t require language and abstract thoughts. Some say that what animals have in their minds are some kinds of proto-beliefs.

Stray Doggo

Here’s an example to highlight this issue. A stray dog is roaming around on the street, looking for food. It comes across a place where some humans have thrown some trash. Its sense of smell leads him to some food. It does this a few times purely based on random searching and following its nose.

Eventually, the dog realizes that this trash dump always has something to eat so it goes straight to the dump every day to see what new food has appeared. Does the dog have knowledge about the trash dump? Does the dog have a belief in his mind that says in dog-speak, “There’s always food at the trash dump.” Or does it hold some kind of proto-belief in its head that reflects the same knowledge?

Plants can Make Choices

Scientists are also figuring out the ability of plants to react to their environment in a way that seems like they’re making a choice. Some plants can sense when a herbivore is eating their leaves and release VOCs that make the herbivore leave the plant alone. Some plants can communicate with other plants through the root structures and choose to share resources. They’ve found that plants are more likely to share resources with other plants that germinated out of their own seeds, so are their kindred, than with non-related plants of the same type.

So do plants have knowledge? They certainly can’t have beliefs or proto-beliefs. That sounds completely counter-intuitive to imagine them having any kind of beliefs. Do we then talk about proto-proto-beliefs?

Or are plants just organic machines who have information stored in their genes about every situation and they’re just running their firmware, not having true knowledge or beliefs? Which brings us to the next issue.

Instinctive, Genetic & Embodied Knowledge

Genes store information that helps individuals survive. If that is not knowledge, then what is it?

What about instinctive knowledge shown by animals such as new born puppies who can’t even open their eyes, but somehow they know to be quiet when their mother is not around and crawl towards her when they can sense her presence and suckle at her teats? Is that also just information in the genes controlling an organic machine?

Like Riding a Bike

What about embodied knowledge such as playing the guitar or riding a bike? Let’s imagine a hypothetical scenario in which a person has a brain injury and loses all memory. They don’t remember anything, even how to speak. But if you put them on a bicycle they can just ride it. Will they be able to just ride it or play an instrument if they knew how to do it before? If yes, then where is that knowledge stored?

Riding a bike is an interesting example because most people don’t truly understand the theory behind how to balance and ride a bike. They just ‘get it’ by doing it. If you ask them to explain how they’re keeping the bike upright, most of them won’t be able to explain at all. And those who give it a try, might not explain it correctly. When we ride a bike, we certainly are not engaging with thoughts about how to ride it, at least consciously. So do we have knowledge about riding a bike?

The Perfect Nihilist

The last issue I want to discuss is the thought experiment about the perfect nihilist. This structure puts all knowledge within the universal set of all beliefs. Nihilism is the philosophy of not believing in anything. That would imply that nihilists can’t have any knowledge either, because all knowledge is a type of belief.

This would mean that all those in the past who were called nihilists by others or by themselves, were not true nihilists because they lived and acted in the world, which needs you to know and believe things.

Let’s imagine a hypothetical perfect nihilist. Let’s call him Fred.

Fred is sitting in a comfortable chair in his room thinking about nothing, when suddenly he achieves perfect nihilist enlightenment.

From this moment on he has no beliefs, and therefore, no knowledge. What will Fred do next? Write an essay on his recent experience? But he doesn’t have the knowledge of writing, language or the existence of other human beings who might want to read his essay.

He doesn’t even have knowledge of himself or that his name is Fred. Fred can’t know where he ends and where the comfortable chair and the rest of the room begins. Fred is just a blissful existence, one with the universe and fully unaware of everything except the present moment. His consciousness has disappeared. There is no ego. He is one with the universe.

But from our point of view, Fred has gone comatose. He can’t move, he can’t speak, he can’t do anything. His body is keeping him alive like a machine but eventually that body will run out of fuel and Fred will die.

Unless his friends find him and admit him to a hospital who hook him up to actual machines that keep him alive. But even then, he’d be in a vegetative state. And let’s be honest, Fred is a nihilist philosopher so it’s not like he has many friends. So, Fred gonna die!

The upside is that it won’t matter to him because he doesn’t have the knowledge of his own existence and won’t feel any pain when he stops existing.

What this thought experiment shows is that as per this structure, a perfect nihilist can’t exist. Because no matter how much a philosopher claims to be a nihilist, their every action, writing essays, sharing their philosophy, discussing things with others, eating food, resting when tired, jumping out of the way of a fast bus etc., will all show that they still have beliefs. Beliefs like when hungry I should eat, or that I exist, or that getting hit by bus equals death.

My New Structure

I start with the universal set of thoughts. These include all the thoughts anyone has ever had and all the thoughts anyone can ever have. Within this universal set lies two mutually exclusive sets of knowledge and beliefs. There is a third set called wisdom that intersects with both knowledge and beliefs and some of it also lies outside both beliefs and knowledge. Here are some explanations about this structure:

- Thoughts and beliefs are different. I can think, “monkeys can fly”, but that doesn’t mean I believe that monkeys can fly. Anyone can use language to construct a grammatically coherent and semantically full sentence that no one has ever thought before, but that doesn’t mean it is a belief.

- The universal set also contains thoughts that no one has ever thought and no one will ever think. This represents a potential space to include any new discoveries in the future.

- Just because I’m using thoughts as the universal set, that doesn’t mean only language based thinking beings can have knowledge, as you’ll see in the next point.

- The set of knowledge contains all kinds of knowledge. Instinctive, genetic, embodied and acquired knowledge all fall within this. The knowledge of plants and animals also falls within this. It lies within the universal set of potential thoughts because even though animals and plants might not have thoughts, we can understand and have thoughts about their knowledge.

- Corollary to above: the set of knowledge also contains certain forms of knowledge that other beings have, that we haven’t understood yet. It’s not human knowledge yet, but it falls within the set of knowledge. This will come in handy when we run into intelligent aliens.

- The set of beliefs contain all kinds of beliefs. True beliefs, false beliefs, justified beliefs, unjustified beliefs, superstitions etc. True beliefs are not knowledge till we understand that they are true and why they are true. True justified beliefs are also not knowledge. These include things we believe to be true but we haven’t verified through empirical evidence or through reason yet. In this structure a belief stops being a belief and becomes knowledge when we verify it.

- The set of wisdom contains that knowledge, beliefs and thoughts that lead to maximizing human flourishing for the most number of humans in the longest run. This is basically my definition of wisdom but we’ll come to that later.

Here’s an advanced version of the diagram to illustrate my point better.

Science is the activity that takes our beliefs and turns them into knowledge. To call knowledge as true justified belief is like calling a butterfly, a post-pupation flying caterpillar. A butterfly is not a caterpillar and knowledge is not a belief. We can have true justified beliefs but they should become knowledge once we’ve understood them through science.

The activity of science involves checking our beliefs to see if they are true or not, finding justification for our beliefs, verifying that our justification is sound or not, continuously updating our theories and knowledge etc.

To explain this let’s remind ourselves of the case proposed by Gettier. Smith’s belief that either Jones owns a Ford or Brown is in Barcelona is a true justified belief but it is not knowledge. In order to turn it into knowledge Smith will have to do science on it and call up Jones and ask him if he has a Ford, to which Jones will reply that he recently sold it and then Smith, to complete his experiment will call up Brown and be surprised to find that he is in fact in Barcelona. Then Smith will have the knowledge that Jones does not own a Ford and Brown is in Barcelona and he can stop using weird sentence structures.

Philosophy is the activity that takes our knowledge, beliefs and thoughts and deciphers how to apply it to our world and our lives. It tries to discover how best to use our knowledge to do wise things.

As mentioned earlier, wisdom will be discussed in more detail later. But for now I just want to say that I recognize other ways of acquiring wisdom including lived experience, faith and spirituality.

The interesting thing about wisdom is that it also contains certain thoughts that are neither believed by anyone nor a form of knowledge. This signifies how sometimes humanity can figure out how to do wise things even before anyone understands or believes, or even thinks it. We can do this through the emergent intelligence of humanity. More on that later.

How this Structure Solves the Aforementioned Problems

All Gettier cases fall under beliefs because the justification is wrong and the person in question hasn’t performed scientific inquiry on their belief. It is not knowledge.

I already discussed the Smith/Jones case above. In the case of the sheep farmer, his belief that there is one sheep in the field is true and he has justification for it but if he did science by entering the field and taking a closer look, he’ll gain knowledge about the actual reality of the situation. All such cases stop being problematic under this new structure.

Animal knowledge is separated from beliefs. Animals don’t need to hold beliefs to have knowledge. They have instinctive knowledge, genetic knowledge, embodied knowledge and they can also acquire knowledge without ever constructing a belief about it.

Moreover, animals might have non-language based thoughts that form a kind of belief, but that remains to be understood better by us humans.

What this system does is that it allows for animal and even plant knowledge to exist without the need for beliefs or thoughts but it keeps the room open for any future knowledge we might acquire about animal beliefs and thoughts.

All forms of knowledge that are not based on beliefs can easily be understood under this structure. And the perfect nihilist can have a ton of knowledge to use even when they stop believing all of their beliefs. So poor Fred doesn’t have to die alone in his comfortable chair.

Objection 1: Traditional Structure Can’t Be Reframed

The traditional view holds that the relationship between knowledge and belief isn’t just a human model — it reflects an objective structure of reality.

According to this view, saying “knowledge doesn’t require belief” is like saying “triangles don’t require three sides.”

The claim is that belief is inherently part of what knowledge is, and to deny that is to misunderstand the nature of reality itself. This is essentially an idealist stance: the structure of concepts like “knowledge” and “belief” exists independent of our minds and accurately reflects the objective landscape of reality — a sort of metaphysical cartography.

My Response: Rejecting Idealism, Embracing Conceptual Tools

I reject this idealist framing. Concepts like “knowledge” and “belief” are not out there in the world like physical objects; they are part of our conceptual framework — mental tools we use to make sense of reality. Ideas do not have an independent, objective existence. There is only one reality, and all our philosophical terms are just ways of modeling that reality.

If there were some omniscient higher-dimensional being — say, a creator god — I don’t believe it would say,

“Congratulations! You humans discovered the correct metaphysical category of belief. That’s exactly how I designed it. Let me show you the 9D warehouse where we store the Platonic forms of knowledge and belief.”

This sort of metaphysical realism might be fun to speculate about, but I don’t think it’s useful. Instead, I view all metaphysical theories — including epistemology — as metaphors for reality. They are lenses, not blueprints. The question is not whether our current framework is metaphysically “correct,” but whether it is useful, internally coherent, and open to revision.

If a new way of framing things — like separating knowledge from belief — allows us to think more clearly, resolve contradictions, and build more robust philosophical systems, then it’s worth adopting.

For a broader take on how I approach metaphysics as metaphor, see The External World page.

Concepts are not discovered like fossils; they are engineered like tools.

Objection 2: Traditional Structure Shouldn’t Be Reframed

This objection isn’t about whether the traditional structure can be changed — it’s that it shouldn’t be.

The claim is that the current belief-based model of knowledge is already well-functioning. Either the problems I’m attributing to it don’t actually exist, or the alternative I’m proposing doesn’t solve them — or worse, introduces new issues that outweigh any benefits.

In this view, the traditional model may not be perfect, but it’s still the best we have.

My Response: This Is an Iterative Step

This is a fair objection, and I welcome any arguments that highlight flaws in my reframing or defend the traditional structure more effectively. At some point, I’d like to dig deeper into a full comparative analysis — but that’s not the aim of ItRaP 1.0.

The structure I’m proposing is not claimed as final truth. It’s a working model — one that I’ve found more useful for solving certain philosophical tensions in epistemology. Since Iterative Rational Philosophy doesn’t require perfection before progress, I’m choosing to move forward with a reframing that seems to offer greater clarity and flexibility for now.

That’s how iteration works: try, test, refine, and — if needed — replace.

In ItRaP, a structure doesn’t need to be perfect — just better enough to move the conversation forward.

Objection 3: Knowledge Without Belief Is Incoherent

How can you know something without believing it? This sounds incoherent. If someone doesn’t believe a proposition, then in what sense do they “know” it? Doesn’t knowledge require at least some form of internal acceptance or belief?

My Response: Knowledge Replaces Belief

This objection only sounds forceful because it smuggles in assumptions from the traditional framework. I’m trying to separate “I know” from “I believe” but that doesn’t mean “I know” now becomes “I don’t believe”. I know that 2+2=4. That doesn’t mean that now, I don’t believe that 2+2=4. The question of belief, positive or negative, doesn’t arise at all because I know this.

If we step outside the traditional structure, the picture becomes clearer. In my epistemology, knowledge is not defined by subjective acceptance. It’s defined by alignment with reality — and the capacity to act effectively on that alignment.

There are many examples where knowledge arises without belief, like in accidental scientific discoveries. Often, a scientist stumbles upon something they did not believe or even expect. They didn’t believe it before the discovery, and sometimes, they still don’t believe it right away — but the data now supports it, and the discovery becomes part of our collective knowledge.

In my system, belief is something you need when you don’t know. Once you know, belief becomes redundant.

This reframing resolves philosophical headaches by recognizing a clearer division of labor:

- Belief is subjective, interpretive, and uncertain.

- Knowledge is objective, functional, and tested.

The two serve different roles. And that’s why I keep them separate.

Summary

Since this is a reframing claim, I don’t need to say any more than this. You can leave a comment if you’d like to raise another objection or help me see where I’m wrong. To continue you can go back to the Epistemology page or the ItRaP page.

Leave a comment